Whenever I plan for a swim in a new body of water, I feel a certain reservation. Shall I trust these waters? Will they welcome me? The wisdom and experiences shared by other swimmers might give me an inkling of the kind of reception I might expect, but there is no telling until the moment the waters and I meet. Some waters have an instant chemistry with a swimmer. Perhaps the setting, the color, taste, and smell—even the weight—of the water, the way the sun reflects on the surface, or the latent power of endless water molecules moving in unison make a swimmer fall in love instantly. But other times, waters can be reserved and mysterious, not wanting to open up to a relationship, at least not right away. The latter is the case of the Mighty Hudson and me.

Encouraged by a dear friend, I decided to include one of the 8 Bridges swims in my season. 8 Bridges is a favorite of the marathon swimming community for the immense challenge it represents—at 120 miles the longest stage swim in the world—but also due to its impeccable organization and dedicated volunteers. My friend suggested Stages 3, 4, or 6 were more suitable for a newcomer. Being a fool for scenery, I picked Stage 4. I couldn’t pass up the opportunity swim by the U.S. Military Academy. The U.S. Army has been a part of my family for three generations.

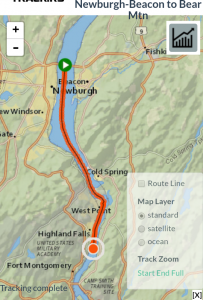

Most people think of the city whenever New York is mentioned, but what they’re omitting is the natural beauty of upstate New York. The Hudson River Valley has always been a favorite of mine. Driving to the Garrison Metro-North Station through winding roads lined with lush trees was a beautiful prelude to what I expected would be a beautiful swim. The morning of Stage 4 was misty, with air temperatures in the lower 70s (21˚C). A group of about 50 people—swimmers, kayakers, and volunteers—boarded the train en route to Beacon, our starting point. From the Beacon Station one can see the Newburgh-Beacon Bridge in the distance.

Next to the ferry dock is a boat house where the kayaks were stored after Stage 3. While the kayakers readied their craft, swimmers handed them their feeds and gear. By day four, many swimmers had already established a routine with their kayakers, particularly the intrepid nine who were swimming all seven stages. The through swimmers were five Americans, three Brazilians, and one Mexican, and one could tell these people had already forged a bond among themselves. One couldn’t find a more fun elite group of swimmers. I felt fortunate to be starting that day, not only because I’d be swimming for the first time in the Hudson and seeing West Point from the water, but also because there were many friends who were starting with me or volunteering, swimmers whom I’d met in Vermont and Arizona during the past year. I love the traveling circus atmosphere.

After checking in with my gracious pilot, Lizzy, I covered any exposed skin with zinc oxide. The day was overcast, but avoiding any potential sunburn is always a priority. The swimmers boarded Launch 5. We motored over to the Newburgh-Beacon Bridge while the kayakers made their way from the boathouse.

I glanced south at the wide river. In the background, the Hudson Highlands were shrouded by the lifting fog. I gazed again at the river. Her gray-green, choppy surface pried my eyes away from anything and anyone. Underneath the waves, I could see the sheer power of the Hudson on its inexorable course south and I understood that it is called mighty because the instant I dove in, she would engulf me and punish me and either humble me or forgive my trespassing and let me go just as easily as it let me in. The mood in the boat was festive, but I’d picked a spot on the port gunwale to take the experience in quietly. Only one other silent swimmer stood beside me. I offered the Hudson a rock I’d picked up on the shores of the Chesapeake Bay the week before. I had forebodings that it wasn’t enough to entice a welcome from the river. Perhaps I should’ve also offered a pink shell from Florida. Neither here nor there, the rock was all I had. I kissed it and threw it overboard.

The captain stopped the boat under the bridge. I looked up at the twin spans and recalled the Chesapeake Bay Bridge fondly. I knew that unlike the Chesapeake, these weren’t known waters; this wouldn’t be an easy swim, but I was determined to find it in me to finish it. Swimmers jumped in the water with glee. I was the last off the boat. Below the surface, the water was dark green and the visibility low. It felt very comfortable at 69˚F (20.6˚C). Lizzy and I found each other right away and soon I heard a loud ‘Go!’ I was grateful I didn’t have any time to consider how the swim would turn out.

Downriver Lizzy and I headed hugging the east bank. She was a fabulous paddler, smooth and steady, keeping her craft pointed on course through chop and wake. Throughout the first four and a half miles of the swim we were hit by unrelenting, deep head-on waves. On my left Lizzy guided me and on my right land features and barges passed by, but these were images that only existed in my subconscious, for I felt I was alone with the river and I belonged in its cool waters and breathing had turned from something vital for land dwellers to something amusing for water beings. The Hudson was punishing me, but she was still letting me through.

Lizzy pointed Bannerman Castle. The river narrowed after another mile at Breakneck Point. As we entered the Highlands the waves calmed. Further downriver, the wind died in the shadow of West Point. When we reached World’s End, just before passing West Point, we crossed the channel over to the western riverbank. Now the river enticed me with pleasantries like a fast current, lenses of cold water, and the magnificent views of the stalwart granite buildings of the Military Academy. The elation was not to last long. As I had expected, once past West Point, at nine and a half miles, the wind picked up and the river renewed her pummeling, invigorated. White caps, fast and shallow, hindered my progress. Every so often my arms would be knocked into a wave, but rather than fight it, I would dolphin through it. Gusts created ripples over the waves and filled the air-water interface with more oxygen than my lungs could breathe. Slowly Lizzy and I traversed the river. I stopped for a feed and looked back toward the Military Academy’s buildings. I was dismayed at how close they still were. Lizzy informed me that we only had two hours left before the tide turned and any remaining swimmers far from the Bear Mountain Bridge would be pulled. I judged I had another five miles left and realized I would never make it. Lizzy and I resumed our toiling while barges placidly sailed by. Lizzy took me into the wind shadow of the small peninsula of Con Hook. My goal was to swim to it so I could at least have a peek at the Bear Mountain Bridge that lay beyond. The safety vessels informed Lizzy the RDs would pull me. I swam nervously waiting for someone to actually tell me to stop. I paused to ask Lizzy when this would occur. She offered I could stop out of my own volition, but I declined. In the shallows near the shoreline the water was warm. My hand touched the bottom and it receded. It felt like a living, gelatinous, dormant creature, which briefly scared me. Lizzy guided me around the north side of the peninsula. Once we turned the corner, the safety vessels were waiting for me. The image of Cerberus appeared in my mind’s eye. I have never accepted defeat so readily. The Bear Mountain Bridge loomed three miles away. I’d swum twelve. The Hudson, gray and angry, impeded the way. I asked Lizzy if I could swim to green marker 35, only because that way I would know the exact endpoint of my swim. It was only fifty yards away, but it took a while to reach it because now I could feel the full brunt of the incoming tide. The Hudson, humoring the idiosyncrasies of an engineer while relishing in her power, declared it was finally time for me to leave. Humbled, I thanked her for the safe passage and touched Lizzy’s kayak. My swim was over.

A few days later, back at my team’s pool in West Palm Beach, I spoke with my dear coach about what this DNF means. He reminded me that I have lofty goals and with those come harder races, some of which I might fail. Improvement is made by taking on races that seem just beyond my reach, not by taking on the ones where I have a high likelihood to succeed. He reminded me of the words of Michael Jordan, whose work ethic and dedication I hold in high regard: ‘I’ve missed more than 9000 shots in my career. I’ve lost almost 300 games. 26 times, I’ve been trusted to take the game winning shot and missed. I’ve failed over and over and over again in my life. And that is why I succeed.’ My coach asked me if I’d do Stage 4 again. I said I would.

Originally posted in Blue Mermaid.